By XY Zhou

Ocula Magazine

One too many Thursday gallery crawls and opening-night parties in the Lower East Side have left me trudging to work on Friday morning, still waking up on my feet. Instagram profiles including thirstygallerina (self-described as ‘NYC’s most spirited gallery opening listing’ with 130,000 followers) reinforce art-world events as a vehicle to get wine-drunk on a weekday, and to partake in the glamorous nightlife of the young artists being catapulted towards stardom.

I don’t believe that being an artist necessarily means you have a higher propensity for substance-use disorders, but there is undoubtedly a correlation between substance use and the creative lifestyle. Or maybe it’s the other way around: perhaps people who are disposed to alcohol or drugs are also drawn towards art. Art is obsessive, and offers an alternative to intoxicating substances in the search for answers. Art offers a way of coping with the world, a way of building community, and a way of healing.

And if you take the life of an artist (or really anyone creative and sensitive) and situate them in New York, with its endless supply of addictive substances, it can be dangerously—even life-threateningly—overpowering. East Harlem and the Bronx have statistically faced the highest rates of opioid-related deaths in the city, largely due to unequal access to resources that make recovery possible.

The deadly opioid crisis that has blighted the United States. since the mid-2010s was highlighted by photographer Nan Goldin’s much-publicised war on the billionaire Sackler dynasty, whose company, Purdue Pharma, was responsible the highly addictive drugs being circulated to patients. Goldin herself suffered from opioid addiction after being prescribed OxyContin in 2014 following a wrist injury.

2024 marked a turning point: the first significant decrease in opioid overdose deaths in New York in nearly a decade. But why? The change could be attributed to three organisations: Odyssey House, Phoenix House and Fountain House. Scattered throughout the city, they combine clinical and holistic care to treat substance use.

Over the past decade, artists and the services they can offer have carved out a new role as part of evolving models of treatment for addiction. This goes beyond art therapy. Treatment providers are hiring curators, artists (like myself) and other creative practitioners to work with clients, with the goal of creating legitimate pathways to art careers for those in treatment.

Odyssey House is one such provider, with inpatient and outpatient treatment sites, supportive housing and community centres throughout the Bronx, Manhattan and Randalls Island. The art department at Odyssey House, where I currently work, has eked out its place in the organisation over the past 25 years. The scale and scope of the operation, with five functioning studios, outreach workshops, museum trips, and a semi-annual art show, are a testament to the central place occupied by art services as a core part of Odyssey House’s mission to enable individuals overcome substance use challenges through working together to support one another.

Byron C. makes a painting for an upcoming show at the Odyssey House Manor Art Studio. He works with plaster and various found objects to create three-dimensional surfaces.

I spend most of my time at Odyssey House’s site in East Harlem, an innocuous, red-bricked building on the tree-lined 121st Street. On the second floor, the bright light, rhythmic beats of KEXP radio, and colourful clutter leak into the linoleum-tiled hallway, inviting clients to peek into the art room. By the time I clock in each day, Chad Porter, Odyssey House’s expressive arts director, has blown through the room like a hurricane, organising art supplies and showing clients new painting media that they may not otherwise have encountered. Porter, wiry, liable to wear all black, and antsy in pursuit of his next artistic endeavour, tells me: ‘Many of our clients had never painted before entering treatment. They discover at Odyssey House that they are artists and take that with them.’

At Odyssey House, art becomes the day-to-day business of clients and staff alike. There’s a handful of regular clients, such as Byron C., who huffs and puffs his way through different projects involving paint and clay. Byron is an avid fan of horror and was originally painting some pretty dark pictures—while not necessarily based on true crime, some of his pieces commented on violence against Black people in the U.S. He regales us with stories about growing up in the Upper West Side, sneaking into concerts at the Beacon Theatre, and skating in empty pools in New Jersey. We crowd around a computer to watch an ancient Super 8 film of young Byron weaving between cones and shredding the hills at Central Park. Over the months, inspired by the art books and postcards strewn across the room, Byron’s work has become more colourful, although the macabre slant remains.

As the day passes, slanted rays of sunlight creep in, crawling across plastic tables that buckle under the weight of paintings, plaster and ceramic objects. This effect is mirrored by a painting that has been tucked carefully behind the door. A man, with his hands in his blue jeans, stares across a chequered expanse to a doorway with the sky pouring in. An ascending slab of stairs blocks the sun, and the sky, and a duo of white-eyed flowers guards the doorway. The stopped clock points forever at 2pm, a hint that time stands still behind these walls. So much feels out of control for clients going through the system, but here, Porter reflects, they are in control of the ‘artistic direction of their expression’. Porter began as an intern at Odyssey House more than 15 years ago; he stays because of the stories, the energy, and of course, ‘believing in the work’.

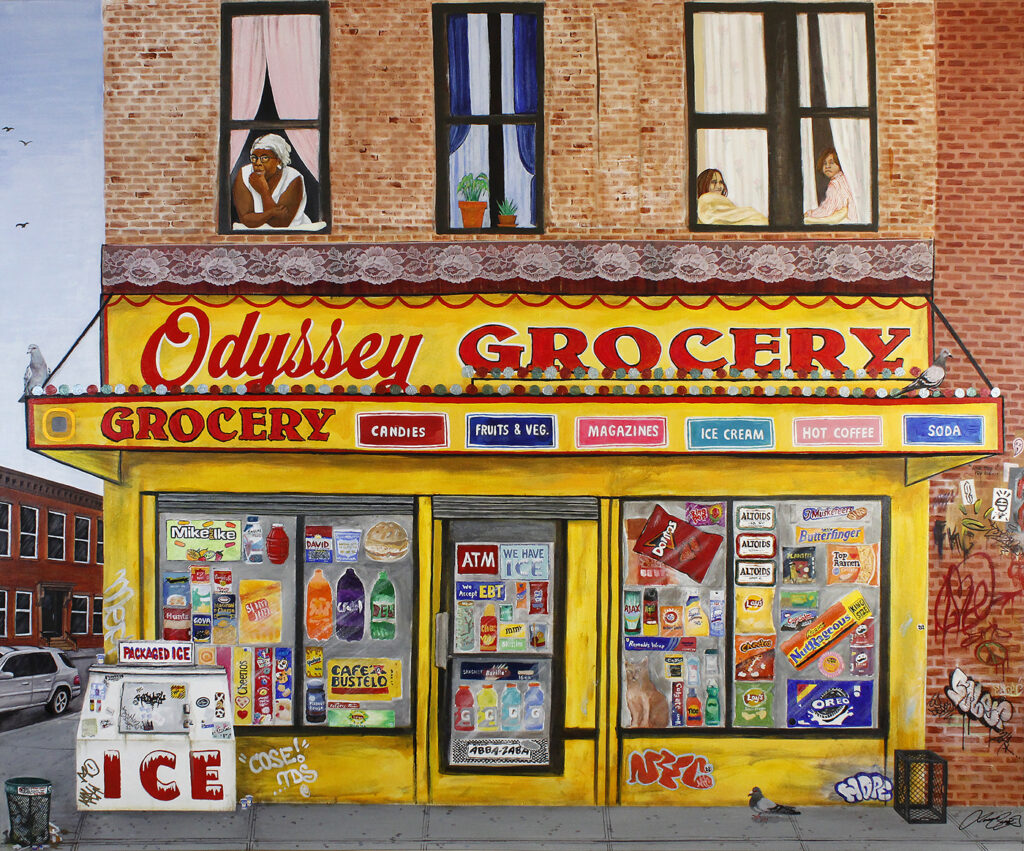

While Odyssey House’s art services are concentrated within treatment facilities, Phoenix House, another New York-based organisation tackling substance use, focuses on bringing art and recovery to the local community. My former morning walk from the Nostrand Avenue station to work brought me through the colourful intersection of Crown Heights and Bedford-Stuyvesant, where I was briefly employed by the Phoenix Houses of New York and Long Island, in the Art of Advocacy Program (AoA). Phoenix House has provided recovery and substance use treatment services for 50-odd years. The Art of Advocacy Program is a part of the Brooklyn Community Recovery Center, one of the first community-based centres in New York State, which addresses substance use with art workshops, creative residencies and wellness education, alongside the standard recovery-group offerings.

This arts- and community-oriented branch of the organisation supports long-term recovery through peer services, especially working with ‘artists who are in recovery themselves’, according to the senior program co-ordinator Zoë Fitzpatrick Rogers. The Art of Advocacy Program is funded by a grant from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), which had nearly $2 billion slashed (and then promptly reinstated within a 24-hour period) by the Trump Administration earlier this month. I’ve seen firsthand the way access to the arts has improved people’s lives, but we still ride a tenuous line when it comes to funding for recovery services. Fortunately, both the recovery and art communities are no strangers to riding through periods of turmoil.

In fact, the workshops bring together an eclectic group of participants who are champions of their own recovery: clients coming from inpatient or outpatient treatment, a rambunctious posse of Caribbean ladies, and outspoken locals who have seen Bedstuy grow and change. Though they rarely consider themselves artists, participants’ work is included in an annual show put on by the AoA team. The cosy Recovery Center, with exposed brick and dark wood ceilings, is decorated with artworks made by the community (and celebrating its resilience).

A banner left over from Breast Cancer Awareness Month and a large quilt of pieced-together slogans from the NAMIWalks (National Alliance on Mental Illness community walks) hang on the walls alongside vestiges of past workshops, reminding us that we ‘Recover Together’. The art workshops bring out their participants’ playful, experimental side. Laughter rings out and occasionally a spontaneous karaoke session fills the air with music. The proof of the community members’ ability to survive, persist and thrive under spiteful conditions is splashed across all the walls.

In contrast to both Odyssey House and Phoenix House, Fountain House Mental Health Clubhouse employs a very different approach to presenting its members’ works to the public. On the busy corner of 9th Avenue and W 48th Street in Hell’s Kitchen, Fountain House Gallery is open to the public five days a week. The front desk is manned by one of the members of the clubhouse; after I exhaust his patience with a barrage of questions, he directs me to the back of the gallery, where the Fountain House staff sit behind half-height walls.

The walls are a part of the ‘social design’ that keeps visitors and members engaged and the gallery staff accessible, according to gallery director Rachel Weisman. As we are talking, another clubhouse member, Maxx, walks right up to show us his latest artwork and submission for the next show: a collage of photos taken from an album he found discarded in his building. Maxx points out the drawings he has on display in the current show of small-scale works, all of which are up for sale, with the proceeds going directly to the artists.

Fountain House was the originator of the ‘clubhouse’ model during the early 1940s, when a group of patients at Rockland State Hospital voluntarily banded together to support one another in their mental health recovery. Tablet Magazine recently covered what it dubbed the ‘enigma’ of the success of the organisation’s clubhouse model, which is sustained entirely by the members: people with serious mental illnesses (SMIs), who live, work and socialise within the Fountain House ecosystem. The model they pioneered has since been adopted by hundreds of other organisations around the world.

Fountain House’s dedicated gallery evolved from a member-driven initiative to create space for art. But the work goes further art therapy derived from the process of making: Fountain House has presented finished works by its members in commercial settings including the Outsider Art Fair and the Open Invitational: Miami. The gallery also puts a focus on providing scholarships and opportunities for artists to gain work experience and, most importantly, show their work within the wider art-world ecosystem. The narrative agency is in the hands of the artists.

Weisman (whose polished outfit and precise vocabulary are clearly of Art World ilk) laughs when I ask her about presenting clubhouse members to the capital ‘A’ Art World. ‘It’s kind of a hard nut to crack, right? With someone’s diagnosis or someone’s substance use history, at what point do you get to be Patti Smith with that, and at what point are you not?’ she reflects. ‘There might be some concrete variables, and it might also just be luck.’ Fountain House’s work appears to be creating luck for its community after years of being down on it.

The romanticised version of the tortured artist, whether alone in their studio or out in society, is certainly alluring. At the same time, other issues are idealised through myth. SMIs, substance use, and housing and career shortages seriously affect large swathes of the New York City population. At that intersection are people and nonprofits that acknowledge art as a tool for the people. In substance use and mental health treatment spaces, art becomes a means for people to distil their thoughts and amplify their ideas. It also brings people together.

‘The more access our clients have to art services, the healthier we are as a recovery community,’ Porter tells me. And we are nothing without community. Creating together helps break cycles of substance use and helps those in need to recover together. —[O]