By Alison Knopf

Alcohol and Drug Abuse Weekly

When we visited Damian Family Care Centers’ Wards Island facility in New York City, collocating addiction treatment services run by Odyssey House and a Federally Qualified Health Center (FQHC) run by Damian, all we could think was: “Why isn’t this done everywhere?” Damian originated as a part of Samaritan Health Services but is now an independent not-for-profit corporation. It is run by people who are committed to addiction treatment and recovery. Peter Grisafi, CEO of Damian, and Henry Bartlett, vice president for government and community relations, collectively have more than 75 years in the addiction treatment arena. Similarly, their colleagues at Odyssey House, Peter Provet, Ph.D., Odyssey House CEO, and John Tavolacci, Odyssey House COO, have long careers in the treatment field and embrace the Damian/Odyssey partnership as the right model for providing health care and substance use disorder treatment in an integrated setting. We visited on March 6.

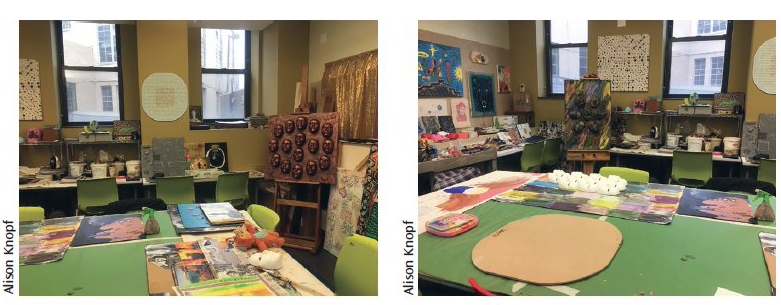

The Wards Island program is, Tavolacci said, the “Taj Mahal” of publicly funded treatment centers. We have visited about 50 treatment centers and agree (see photos of the art studio, below). There’s a gym, art studio, bedrooms that rival any college dorm room we have seen, views, child care (including for babies) and on-site health care.

Damian had help: the New York State Office of Addiction Services and Supports contributed $28 million to the construction of the Wards Island building. But that’s where the help ended: The rest of it is smart people using New York’s generous Medicaid program, the release of liability based on tort reform and the vision of people who have worked in the system long enough to know that if you don’t treat a person’s addiction, they won’t get well in other ways either.

Damian Family Care is a network of 15 centers located in New York City and Long Island, and expanding into upstate New York. “We have a specialty in treating people who are going through recovery,” Grisafi told ADAW. Often patients graduate from addiction treatment but come back for health care – either at the collocated site or at one of the other sites (there are 12 sites with collocated addiction treatment and health care). Damian treats more than 12,000 patients a year, more than 6,000 of whom are in a collocated model where the FQHC partners with an addiction treatment program. There are referrals from site to site – for example, for optometry, neurology or pain management, which aren’t at every site. Damian transports patients from site to site for services that aren’t available.

The Wards Island facility is only for residents of Wards Island.

At Wards Island, primary care, OB-GYN and oral health (dental) services are offered.

Sliding scale

Treatment is available on a sliding scale. Anyone below 200% of the federal poverty level (FPL) is slid down to a reduced fee, and anyone below 100% of the FPL gets the service for free. This includes prescriptions. “We know that people going through recovery have a high percentage of HIV and HCV,” said Grisafi. “We treat more than 800 people a year with HIV or HCV.” The medications for these conditions work but are expensive.

Odyssey House would have always paid for someone’s medications for HIV or HCV, but now that an FQHC is involved, they don’t have to do that, explained Grisafi. “They no longer have to pick up that tab,” he said. “We pick up the tab.”

Full retail for Gilead’s hepatitis C medication is about $60,000.

“We at Odyssey House have seen oral health as important to treating the whole person,” said Tavolacci. After medical services, evidence-based addiction treatment and the whole process of recovery, if a patient goes to a job interview and has no teeth, the prospective employer wonders “How can this person represent our organization?” he said. That’s why Provet is so committed to dental services. Provet “was the champion in creating the first dental clinic at Odyssey House,” said Tavolacci.

Provet, who started at Odyssey House 20 years ago, worked for Phoenix House before then. At the Yorktown Heights Phoenix House facility at the time – a beautiful campus at the time (200 acres) with houses – the program had a dental facility. “People looked at us like we were nuts,” said Provet. “At that time, medical care was barely given to clients.” But the dental chairs were made so that the clients could look out the window at the pasture. “Many visitors were stunned,” said Provet. “There was almost a feeling, even from some funders, like ‘These clients, they really have it good, these poor people who were living on the streets.’” The driving force, said Provet, was to create an environment of dignity. (Damian is also a provider for Phoenix House – one of the collocated sites.)

TCs collocating with FQHCs

This was the model for the programs like Samaritan Village, Phoenix House and Daytop – the residential addiction treatment programs commonly known as therapeutic communities (TCs).

“This is the movement,” said Tavolacci. “We all had this vision of doing a biopsychosocial model.”

How is this financially viable? There are some grants from the federal government. “We get the wraparound rate from Medicaid,” said Grisafi. The patient population is 85% Medicaid. “That’s our best payer,” he said. “That’s where the non-FQHC providers are – they don’t want Medicaid. There are regulations the FQHC has to adhere to. For one thing, the board must be a majority of patients of current health centers; this must be demonstrated to the federal government – “not just coming in for a flu shot,” said Grisafi. Finally, the government covers the FQHC in the Tort Claims Act. “We don’t have to buy malpractice insurance for our providers,” said Grisafi, noting that this cost is very high for OB-GYN. The government doesn’t buy health insurance for the FQHCs, but actually covers them.